The day after Mother’s Day (in the U.S.), I’m thinking about my own mother, whose long-term memory is still sharp as a tack. My mother remembers being a young bride in Korea—not the Korea you think of today with high-end electronics and luxe skincare, but the ravished post-war country where people died of starvation. She and my father were raising their first child, who was doted on by the entire extended family.

During that time, she saw a lot of biracial children. My mother remembers babies (mixed and not) being left outside of the wealthier people’s homes.

The hope was that the rich would raise the children that the impoverished couldn’t. And while some were taken in by neighbors, these children were not usually raised as family members, but as servants. Sometimes, if the couple was infertile, the wife would go away for a while and return home with the child and pretend she had given birth to it.

My mom used to tell me about a cute little girl, whose mother was Korean and whose father was an African American soldier. When he left Korea, he promised he would send for them. They never heard from him again. They moved in with the woman’s elderly mother. For five years, my mother watched the grandmother and baby go everywhere together.

And then, one day, the little girl was gone.

“Where’s the baby?” my mother asked.

“We sent her to an orphanage,” the grandmother said. “It was our only choice.”

From today’s point of view, it doesn’t seem like the only option. But back then … because of the prejudice against mixed race children (and the unwed women who bore them), the only chance of survival they had was to marry a man who would take care of them. And no Korean man at that time welcomed a child who was half Black (or white, for that matter) into his family.

As a visibly biracial member, she was forced to wear a hat to cover her Afro when she made television appearances.

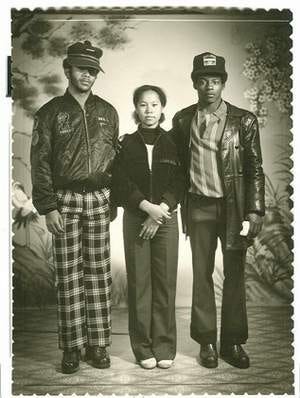

All of that happened many, many decades ago. But my mother’s memory made me think about the Korean R&B singer Insooni (née Kim In-soon) and Ronald Lewis, an American G.I. who befriended the biracial teenager when she was ostracized by Korean society.

And before you start to worry, don’t.

There was never anything inappropriate between the two. Lewis said he had experienced racism in the U.S., but hadn’t expected it in other countries. When he saw it happening to Insooni in Korea, he and his friends took her under their wings, buying her food and trying to make her life a little easier.

Due to bullying and financial difficulties, Insooni’s formal education ended after middle school. It was with that in mind that in 2013, she founded the Hae Mill School outside of Seoul. The institution offers free tuition for biracial students.

Insooni had made her professional singing debut with the girl group the Hee Sisters in 1978. As a visibly biracial member, she was forced to wear a hat to cover her Afro when the group made television appearances. Two years later, she jumpstarted her solo career.

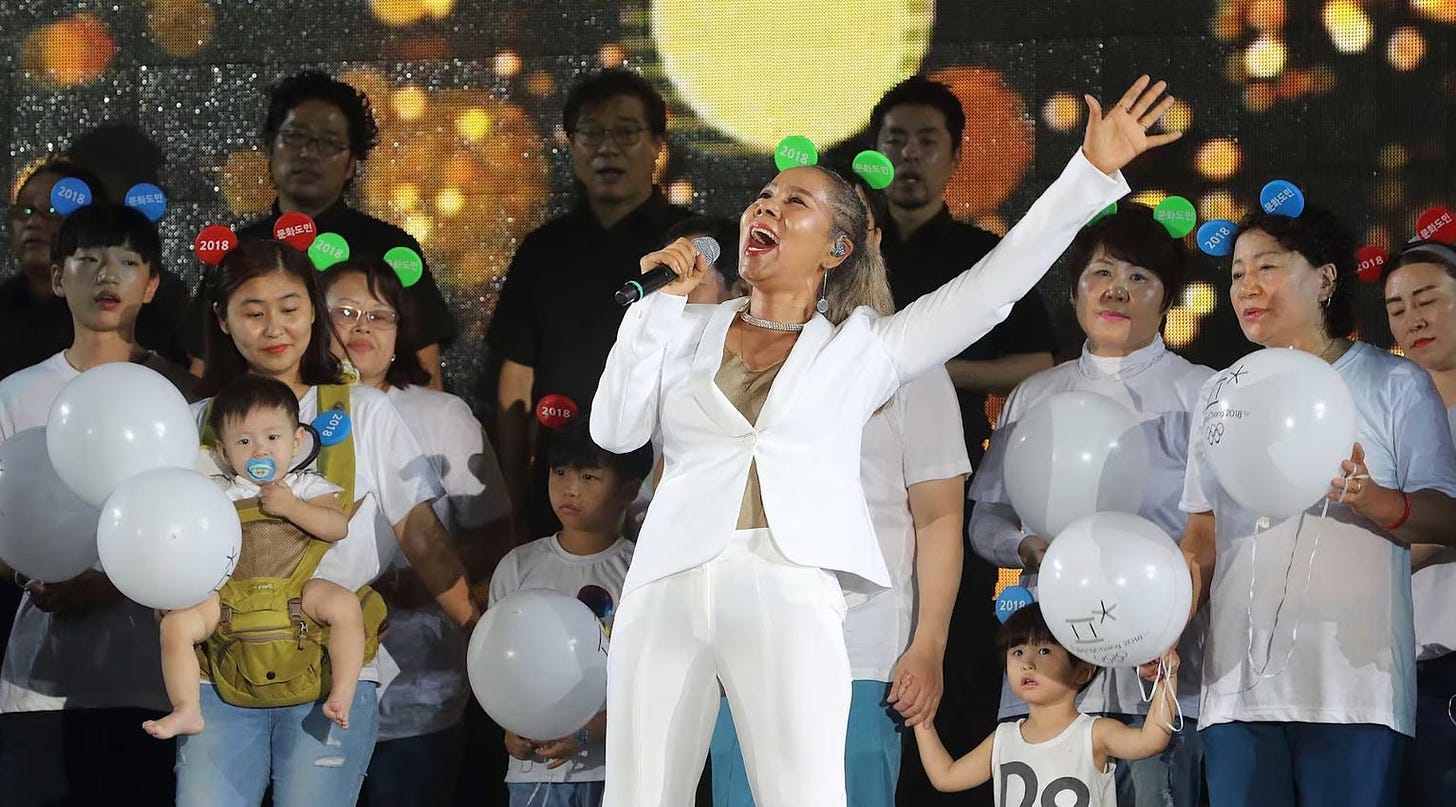

In 2017—200 days prior to the start of the 2018 Olympic Winter Games in PyeongChang, South Korea—Insooni was invited to perform the Games’ theme song, “Let Everyone Shine” in Chuncheon. She also was selected as an ambassador for the Paralympic Winter Games.

Though the singer, now 67, hasn’t released any new material since 2015, she was a judge in 2021’s “Hello Trot” and a cast member on last year’s “Golden Girls.”

And, yes, Insooni is a mother. She and her college professor husband Park Kyung-bae share a daughter, Park Sae-in (who, incidentally, graduated from Stanford University).

I hope she had a very happy Mother’s Day.

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

Thanks for sharing this story—it's a reminder that Korea's past is not so distant and yet how far they've come so quickly. But clearly, still not far enough when it comes to some social issues (like the fact a baby can still be sent out of the country to be adopted). I recently watched 12.12: The Day and am watching Citizen 1958, and looking forward to Uncle Samsik—all because I want to know more about the history of this period. A couple nights ago I stumbled upon the slides my mom used when she gave presentations trying to get others to adopt Korean babies. It made me understand why I had the picture of Korea seeming more like the North Korean village in CLOY in my mind all these years.

I'm glad to hear Insoon was able to rise above her circumstances and have success in both her personal and professional life. No doubt it wasn't easy, but it goes to show that not all orphans and/or mixed kids were doomed if they weren't sent away from their homeland. My parents were told I was mixed, but in 2014 23andMe told me otherwise. Now, I wonder if the "mixed" thing was a narrative used to justify sending even more babies out of the country. People questioned me my whole life when I said I was mixed because they didn't think I looked mixed (that's a whole different discussion). As a mixed baby I was doomed to become a prostitute—something one of my sisters reminded me of not so long ago (sigh). But without that (hyped) narrative what was the reason I needed to be shipped out?

What if? You asked that question recently on IG. I would go back and change things if I could. But similar to you I want the wisdom of what I have gained to make those changes—and I also want the magic wand of a K-drama to make it possible for me to have some of the same things without having to make the same choices. ;)

I hope you had a nice Mother's Day. :)

In-Sooni came and gave a speech when I was an exchange student at the Korean Air Force Staff College. Even with her using a crappy speaker and microphone, I was absolutely blown away how beautiful her voice was in person.