Happy Hangeul Day!

The beauty and heartbreak of learning and losing your language

Happy Hangeul Day/한글날! Almost all South Koreans have this federal holiday off on October 9. (North Koreans celebrate Hangeul Day as well, except they do so on January 15.)

I know that some of you who regularly read my newsletter have taught yourself how to read Hangeul. And from the emails and DMs you’ve sent me, I understand that you may not know the meaning of most of the words you are reading. However, you can pronounce Korean words and names better by reading them in Hangeul than the McCune–Reischauer romanization of Korean words.

King Sejong invented Hanguel in the 15th century. His goal wasn’t to inflict another language on his subjects. Rather, he created a 28-letter alphabet that was simple enough for even the uneducated lower class citizens to learn. (Four letters were eventually dropped to its current 24-letter count.) Until then, most books and documents were written in classical Chinese, which was complicated and accessible primarily to only the privileged upper class.

King Sejong wanted everyone to be able to read, write and communicate in a common language. Knowledge would help equalize his people.

Of course, some of the nobles were angry about this. They were afraid the peasants would be able to figure out that they were being taken advantage of.

It had always been my goal to raise my son to be bilingual. It was easy enough when he was a baby. It was natural for him to refer to me as 엄마, rather than mommy. In fact, he liked the word so much that's what he called his father for a long time, too.

Even though I speak Korean, English is my dominant language — just as it is for my siblings. Still, I was able to teach my child things like the "Three Bears" song. He learned his Korean numbers during his taekwondo lessons. And for about two years, he attended Korean school on weekends. (He quit going when it interfered with his basketball games.)

I don't know anyone — immigrant or not — who regrets being bilingual. But I know plenty of people who wish they retained more of their mother tongue.

While searching for leads on Korean language schools and tutors on the internet, I found an old blog post by a woman on Kimchi Mamas that surprised me. She didn't want to teach her children how to speak Korean, but didn't know how to tell her parents:

"I have not and am not planning to teach my kids a lot of Korean. I am not ruling it out. If they have interest, I am happy to teach them in the future or enroll them in Korean school. You know, the dreaded Saturday classes? BUT, I am having some internal struggles on how to reply when my parents or my MIL ask about this subject. They want my children to know Korean. Especially my dad and mom since they don't speak a lick of English."

One of the respondents drove home a point that I shared:

"I know this is a super old post but just thought I'd comment anyway... I don't understand why you would not teach your child Korean? I don't mean send them off to Korean class or anything, but just around the house speak to them in Korean. Another language always comes in handy! I am of Indian origin, now living in Canada, and there are a lot of languages in India (numbering in the hundreds). And basically my parents would just speak to me in a mixture of English and my mother tongue and another state language, which I how I learnt to speak them. I also picked up the basics of another Indian language from watching movies. So... I don't know what the issue is with teaching your kids Korean...they will learn English in schools, so let them learn Korean at home...

It seemed like the original poster was throwing away an opportunity to share her heritage with her children. But then again, hadn't I been doing the same? I had been hemming and hawing about when to send my son to Korean school, partially because my own memories of attending weekend classes weren't great. My parents — who were fluent in Korean — thought I'd learn more in school than if they taught me. So, they enrolled me when I was 11 or 12 years old.

When I walked into the classroom, all the children stood up and bowed to me. They were about 5- and 6-years old. I was easily twice their age and height. They thought I was their teacher.

During class one day, one of the little girls said (in Korean) that I must be stupid. Why else would such a tall person be in their class? The teacher explained that I was actually very smart, but I didn't speak Korean very well, which is why I was there. She also kindly pointed out that I spoke English better than anyone in the room.

I don't remember if I went to Korean school for a year or two. But I didn't last much longer. I was too embarrassed being the oldest kid in class and just refused to go any more.

If I knew then what I know now, I would've kept going. I would've learned to read and write well enough to place out of the language requirements in high school and college. I would've applied for a job in Seoul where my proficiency in both languages would've given me a leg up on the other candidates. And I would've spoken to my parents in fluent Korean, rather than my pidgin version that they were used to.

I don't know anyone — immigrant or not — who regrets being bilingual. But I know plenty of people who wish they retained more of their mother tongue.

I still remember my son’s first day of Korean school. Four hours on a beautiful Saturday morning. And he was just 5. I was worried enough that I peeked through the classroom window during recess to see how he was doing. He was playing alone, and I felt my heart sink, thinking about my days as the lonely new kid in school. I feared that the children — who had been in class together the full year already — might be excluding him. A couple minutes later, I took another look and smiled. There he was, putting together a fort as his classmates brought him building blocks to fortify the building.

This was just a one-off class, since it was the end of the school year. But he officially enrolled when he started kindergarten.

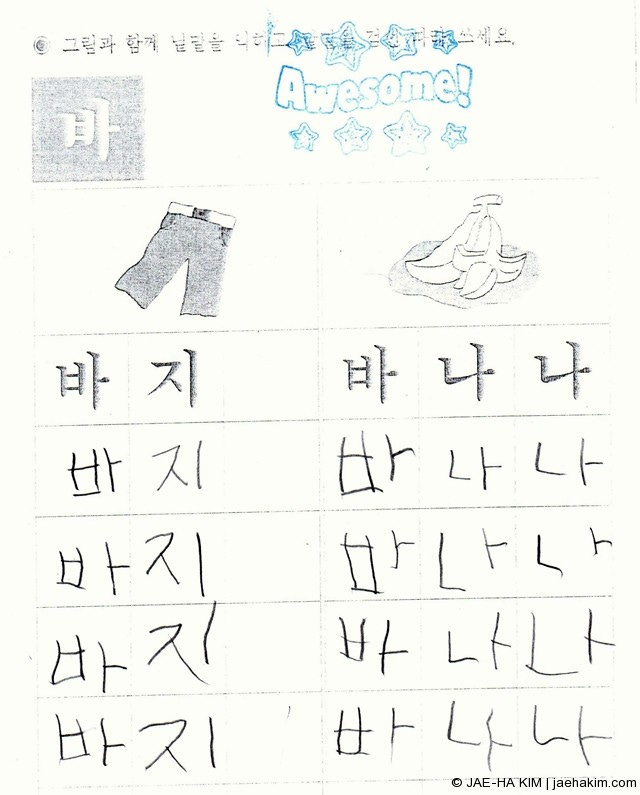

Oh. In case you haven't gotten the hint from the pictures, 바지 means pants. 바나나 means banana.

Pants and bananas. What more did a little kid really need to know, right? LOL

As for the future … well, he’s a young teenager now who’s studying Spanish in school, because our district doesn’t offer Korean (or Mandarin) — just Spanish, German and French, which is pretty behind the times if you ask me.

However, if he shows an interest in wanting to learn Hangeul, he can do what his cousins did: enroll in an immersive summer language camp, or study at a Korean university for a summer (or a full year) when he’s older.

My child had school off today for Columbus Day, which thankfully is also recognized as Indigenous Peoples' Day. Since it’s also Hangeul Day, he made kimchi fried rice for our lunch (and even saved some for his father to eat when he gets home from work tonight). It was delicious.

Happy Hangeul Day, everyone!

© 2023 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

K-DRAMA INDEX

These are some of my reviews and essays about K-Dramas (and also Korean films and other Korean-centric projects). You may also read more about my take on Korean pop culture in outlets such as Rolling Stone, Mashable, Victoria & Al…

language is so important. I met a Nepalease kid recently, and he was sharing with me the ways and means that his people in exile go about a cultural protest...a means of defiance- A way to not be erased even when your country is not your own. Language is one such way.

I have been thinking about being (at least) bilingual for a while now, Jae-ha.

I live in the Philippines, where Filipino and English are the official languages, and many are usually able to speak a third language (a local one, like Bisaya or Ilocano). Up until recently, that third language was being used in schools in the provinces, although use of the larger "thirds" in media is still widespread, so they're perhaps not disappearing any time soon.

Unfortunately, however, the use of local languages—whether it be Filipino, which is a somewhat "constructed" language based on Tagalog but integrating words from other regions to be widely understandable by most Filipinos; or the third languages—are seen through this prism of class and privilege. The better you speak English, as the thinking goes, the farther you can go in life. If you listen to song in Filipino, your tastes must be pedestrian. That sort of thing. Short-minded, if you ask me. I consider myself fluent in English (I write in it almost exclusively) but I don't lose anything by continuing to use Filipino in conversations. I feel freer doing that, even.

And yet I am now seeing children who were raised on Peppa Pig and other English-language pre-school programming, who speak very well in English (complete with the accent) but struggle to communicate with other people in their home language. But then, they're just the "poor" people, right? And you don't want to associate with them, right? And if this continues, well, it's a slippery slope.

I overburdened you with this, I'm sorry!