Sohn Kee-chung Was Korea's 1st Olympic Gold Medalist

But his medal is listed as a win for Japan

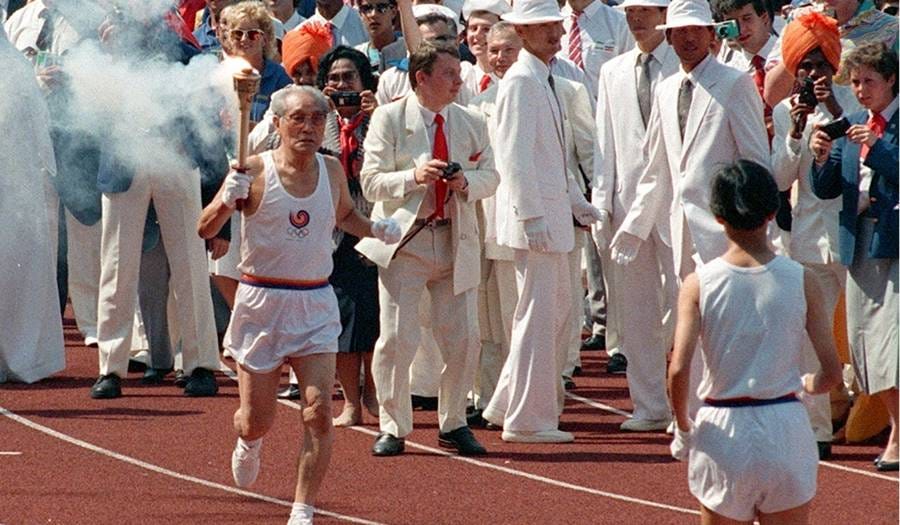

Growing up, I had heard my parents talk about Sohn Kee-Chung (손기정). Sohn was the first Korean to win an Olympic medal, and it was gold. At the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, he set a world record in the marathon. So it wasn’t surprising that when the 1988 Games were held in South Korea, Sohn had the honor of carrying the Olympic torch into Seoul Olympic Stadium (also known today as Jamsil Olympic Stadium).

My parents beamed with pride as they watched the then 76-year-old Korean hero leap for joy and run around the track to thunderous applause. (You can see archival footage of Sohn’s entrance in the first episode of “Reply 1988.”) At the time, I thought he looked like a silly old man. But watching it today with what I know now, I teared up at how meaningful this must have been for him.

When Sohn won his gold medal in Berlin, he had to compete under the Japanese name of Son Kitei. Why? Because Korea, at that time, was part of the Japanese Empire. Koreans were forced to take Japanese names and were ordered to speak Japanese.

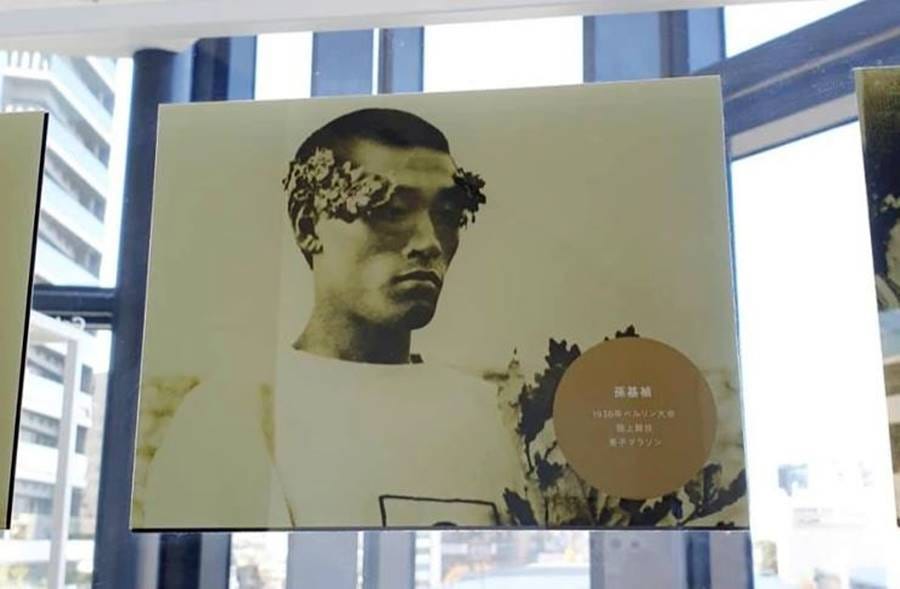

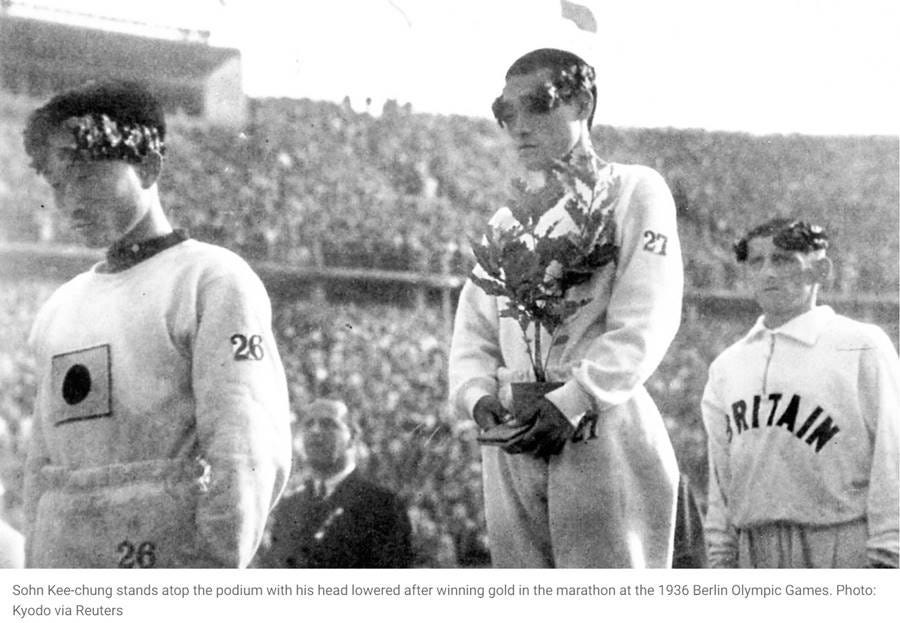

When Sohn stepped onto the podium to be honored for his historic win in Berlin, he tried to hide the Japanese flag on his shirt with a plant someone had gifted him. In his autobiography, 나의 조국 나의 마라톤 (My Motherland, My Marathon), Sohn wrote that he felt unbearable humiliation hearing the Japanese national anthem played for his achievements. (The bronze medal went to his Korean countryman, Nam Seung-yong (남승룡), who also had to compete under a Japanese name (Nan Shōryū).)

My father, who was very young when Sohn won his gold medal, remembered how proud Koreans were of the win, but also how bitter they felt that the world wouldn’t know that the winner was actually Korean and not Japanese.

One Korean newspaper, the Dong-a-Ilbo, tried to right this wrong. They altered the photo of Sohn on the medal podium, so that the Japanese flag was no longer visible. Retribution came quickly. Eight newspaper staffers were arrested and the publication was halted for nine months.

Still, according to his son, Sohn Chung-in, the Olympian chose not to harbor hate. Instead, he had hoped that what had happened in the past wouldn’t be repeated again, and that two countries would fare better in the future.

Sohn Kee-chung died in 2002 at the age of 90.

When I was in high school, one of my best friends was a Japanese American girl. At the time, we knew little about what our parents had lived through, because they didn’t talk much about their difficult past. We didn’t know why her parents were initially hesitant about meeting mine. Because of the complicated and brutal history between Korea and Japan, they feared that my mother and father would be uncomfortable around them.

They told their daughter, “You and Jae are from a different generation and can be good friends. But her parents may not want Japanese friends.”

They were proven wrong, of course, and ended up socializing with my folks. My dad, in particular, enjoyed conversing with them in Japanese.

What I hadn’t realized until I became an adult was that because my parents had been forced to speak Japanese as children, the Korean I learned from them is also peppered with Japanese words. I had always just assumed that I was speaking Korean.

And then it all started to make sense. The time we were in Hawaii and the Korean waitress couldn’t understand what my Korean mother was requesting. The time I was in Korea and had a difficult time being understood by 20somethings — until I spoke in English. The time my young Korean cousin was visiting us in the U.S. and didn’t know what I was saying when I asked her — in (what I thought was) Korean — to put some cups on the table. The time I asked the cosmetics clerk in Seoul for kuchibeni (lipstick) and was met with a blank stare.

I was speaking Japanese many decades after Korea had already won its independence. That is the lasting effect of colonialism.

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

It’s one thing to learn about and understand this in an academic sense and within historical context, but it’s examples such as yours that bring it into sharper focus and make it feel real and tangible.

Thank you for sharing.

This was a fantastic read, thank you. My partner was born & lived in Japan until he was 20, his father is American and mother is Korean - though she grew up in Japan, she will never get citizenship, and neither will he. They are granted “lifelong residency” because of the relationship between Japan & Korea specifically, which has to be repeatedly renewed when living out of the country for more than a few years - and of course covid quarantines created complications with this 🫠 to second Barb above, it really does make a difference to hear personal stories about the infinite small yet HUGE ways colonialism seeps into the groundwater of life for generations after. Thank you for sharing 💗