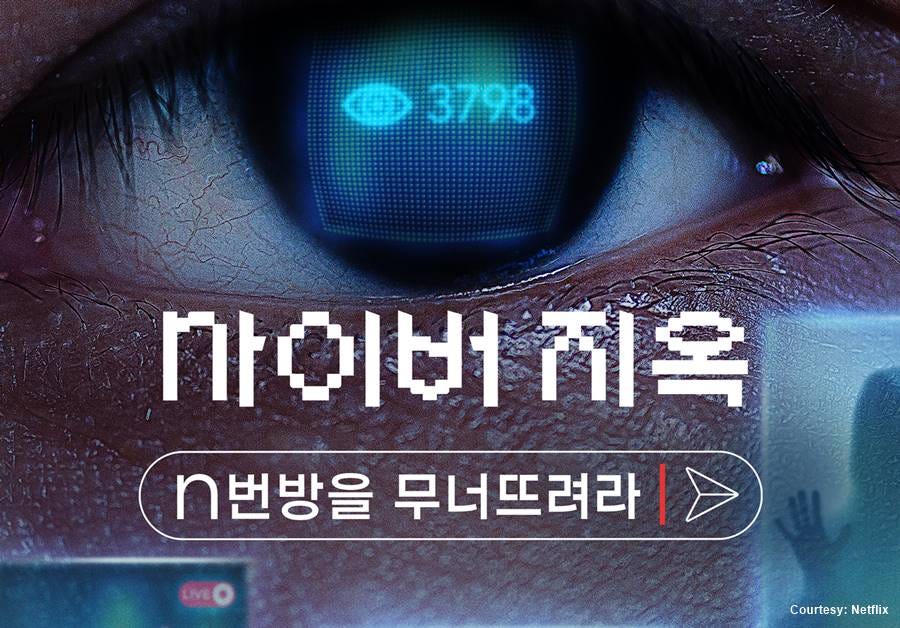

“Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror”

The documentary chronicles the Nth Room, and how South Korean girls and women were blackmailed and tortured

🔺TRIGGER WARNING:

The following documentary review and commentary includes disturbing details about the sexual exploitation and torture of underage girls and young women.

☆☆☆☆

Directed by Choi Jin-seong

From 2017 to 2020, Moon Hyung-wook (known online as Godgod) and Cho Ju-bin (known as Baksa, or doctor) ran a series of illegal channels on Telegram, an end-to-end encryption messaging app that allows 200,000 people to gather in an online room and chat. (By comparison, WhatsApp is set up for a little over 1,000 people.)

While Moon’s Nth Room and Cho’s Doctor’s Room operated different channels, their purpose was the same: con young women and underage girls into sending them nude photographs of themselves, blackmail them, and sell them to their paying customers.

Godgod contacted potential victims on Twitter (now renamed X), telling them that their private images had been leaked online. Once they clicked on the phishing link he had sent, their phone (or other device) would become infected with malware, giving him access to their personal information.

Meanwhile, Baksa posed as a recruiter booking models for lucrative jobs. He asked the victims to send revealing photos, so he could judge whether their bodies were appropriate for modeling gigs. After he pretend-hired the victim, he asked the standard questions that employers need to issue payments: full name and address, resident registration number, and their bank account number so he could wire over their payments.

Of course, the victims never received a cent. Instead, they were blackmailed and threatened. They were ordered to send more photos and videos, this time fully nude and more degrading. If they failed to comply, their name, address, and the first few images they had submitted would be released to their families, friends, and classmates. This cycle of abuse escalated, with both men encouraging their followers to harass, stalk, abuse and rape the slaves.

One slave was forced to make a video of herself shoving multiple pens into her vagina. Another had to thread a needle through her skin and hang objects from the dangling string. One middle school girl was ordered to take off her clothes and lick a filthy public bathroom floor. Still others were forced to carve slave onto their bodies with a knife.

Were these perpetrators simply sadists who hated women? Did they have any loving relationships with women in their lives? Were they able to enjoy these degrading images because they disconnected between a real-life human being and an inanimate object who was there solely for their pleasure?

Watching this documentary, some viewers might wonder: how would anyone fall for this? Ask yourself this: have you ever clicked on an email link (that supposedly was sent by a friend) that turned out to be malware instead? Have you received a call from your bank saying they needed your social security number to safeguard your account? Has a gorgeous young woman (or man) wooed you on social media, and then asked you to send them money so they could pay their mother’s hospital bill?

Even if you haven’t fallen for any of these scams, it happens to others every day. A financial advice columnist was tricked into giving $50,000 to perpetrators. And scammers sexually extorted money from predominantly teenage boys in the U.S. One 17-year-old high school student died by suicide after being blackmailed by Samuel Ogoshi, 22, and his brother Samson, 20. (The Ogoshis were extradited from Nigeria to the U.S. and have plead guilty. Mandatory minimum sentencing will be 15 years, with a maximum of 30 years.)

Baksa and Godgod targeted women in a lower socio-economic class who needed money. They also set their marks on innocent children, who were too young and incapable of handling any of this.

“Cyber Hell” is disturbing to watch, and that is part of its goal. If it’s this uncomfortable for us to view, what must it have been like for the victims?

Director Choi Jin-seong tells their stories without sensationalizing the facts, which are already obscenely disgusting. He utilizes archival news footage, recreates scenarios with actors, and blurs out images of the whistleblowers who wished to remain anonymous. Kudos to a pair of female college journalism students, known collectively as Team Flame, who dug into the rumors and accusations. These student journalists were the first to investigate and report on these crimes in 2019.

When mainstream media finally began to report on the Nth Room and Doctor’s Room, they relied on Team Flame as much as the police to break the case. Interestingly, and also sadly, some of the professional journalists acknowledged that when they first received tips about what was occurring in these online rooms, they hesitated — not because of the prurient topic, but because they had already written so much about molka. In other words, these digital sex crimes are so commonplace that the journalists and editors didn’t think this would be a newsworthy topic for their audience.

FYI: molka is a portmanteau of the Korean word molae, which means unaware, and the English word camera. In Korean, it’s written as 몰래 카메라, referring to miniature spy cameras illegally installed into public bathrooms, hotels etc.

Despite the increase in illicit-filming crimes, the absence of restrictions on purchasing a microcamera reinforces weak initiatives meant to protect the citizens of South Korea. Purchasing a microcamera is not illegal in South Korea. With a simple search for one on the Internet, one can find a small camera costing approximately ₩5,000, or less than 5 USD.

“Cyber Hell” spends a lot of time — almost too much — talking to the reporters who covered this case. There isn’t enough commentary about what is being done to help the survivors. It would have been impactful to hear discussions from psychiatrists and other experts on what can be done to help the victims heal after living through this ongoing trauma. Though some of the men involved have been imprisoned —Cho/Baksa and Moon/Godgod were sentenced to 42 and 34 years in prison, respectively — the victims’ images are still circulating and being sold on the dark web.

I’m reminded of what Epik High’s Tablo told me when we discussed how TaJinYo — an online community of hundreds of thousands of antifans — orchestrated a smear campaign meant to end his career. After years of incessant harassment, some of the perpetrators were sentenced to prison. But that didn’t give Tablo back what they took away from him: time and a sence of privacy and security.

“When I won, did all [the members of TaJinYo] disappear from the face of the planet?” Tablo asks. “No, they all went back to their lives and probably moved on to do it to other people. I’m pretty sure they’re next to me when I’m buying bread, or when I’m buying strawberries, or they’re sitting next to me when I’m at a movie theater, or are doctors and nurses at the hospital I go to. Literally, there were doctors and scientists — legit people in society — who were caught. What I’m saying is they’re all still here. Ninety-nine percent of them walked away without any punishment, like they were walking away from a video game. How can I stop talking about it? How can I stop thinking about it?”

Release date: Directed by Choi Jin-seong, this 1-hour 45-minute documentary dropped on Netflix on May 18, 2022.

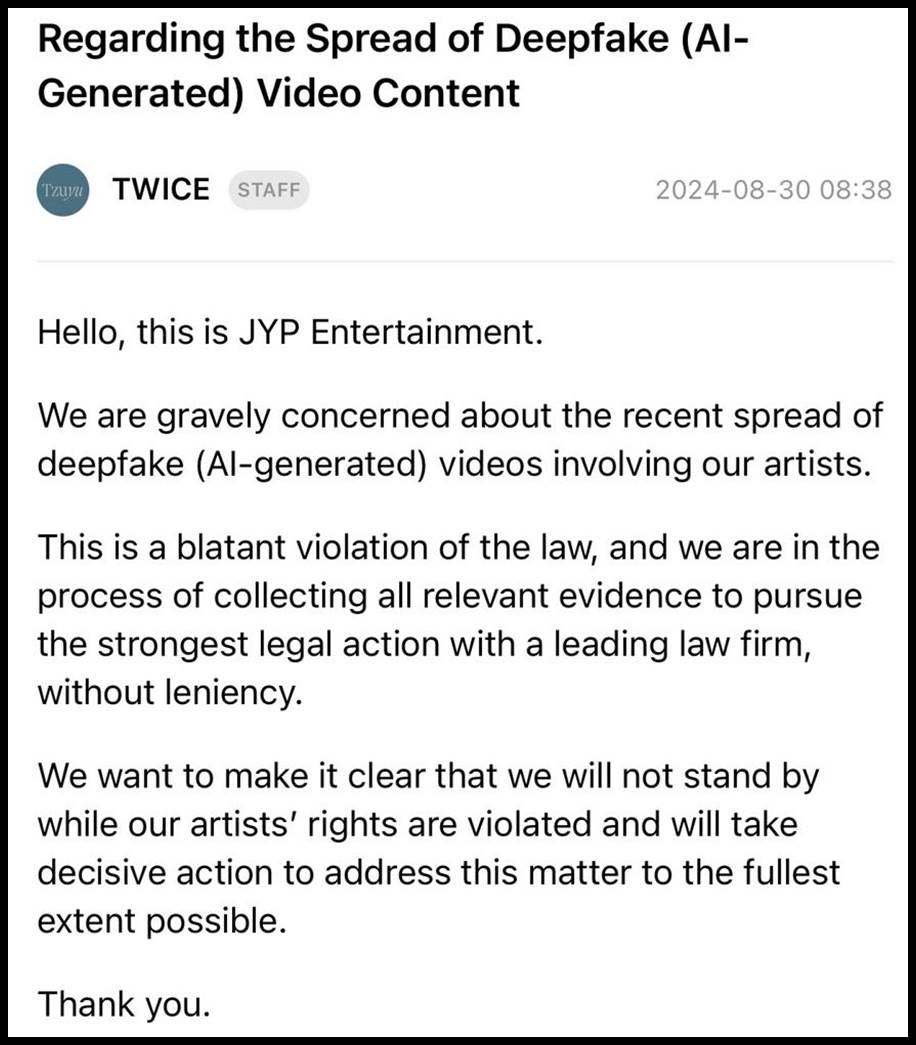

End Note: Using AI technology to create deep fake images of women has been an ongoing issue worldwide. JYP Entertainment — one of South Korea’s largest Big Four entertainment companies — released this notice yesterday stating that they will do everything in their power to protect their artists:

These crimes have become so prevalent that the president of South Korea has urged authorities to do more to eradicate the digital sex crime epidemic:

"Recently, deepfake videos targeting an unspecified number of people have been circulating rapidly on social media," President Yoon Suk Yeol said at a cabinet meeting [on Tuesday, Aug. 27, 2024]. "The victims are often minors and the perpetrators are mostly teenagers."

To build a "healthy media culture", President Yoon said young men needed to be better educated. “Although it is often dismissed as ‘just a prank,’ it is clearly a criminal act that exploits technology to hide behind the shield of anonymity."

The spate of chat groups, linked to individual schools and universities across the country, were discovered on the social media app Telegram over the past week. Users, mainly teenage students, would upload photos of people they knew – both classmates and teachers – and other users would then turn them into sexually explicit deepfake images.

The discoveries follow the arrest of the Russian-born founder of Telegram, Pavel Durov, on Saturday [Aug. 24], after it was alleged that child pornography, drug trafficking and fraud were taking place on the encrypted messaging app.

Bear in mind that President Yoon had previously abolished the gender ministry, said that structural sexism was a “thing of the past,” and won his election by pandering to young men who believed that equal rights for women equated to men suffering from reverse discrimination.

Especially disturbing is the fact that over the past three years, two thirds of the deep fake offenses in South Korea have been created by teenage boys, using the faces of their female family members, classmates, and celebrities to create porn. [Just three percent of offenders aged 14 to 18 are criminally punished for rape and murder.]

Most of the [juvenile] offenders in the older age bracket are also given protective dispositions, such as lectures, community service programs and youth correction institutions. Punishment with protective dispositions leaves no criminal records.

Some K-dramas that deal with digital sex crimes include “Taxi Driver” and “Hotel del Luna.” Also, watch “Juvenile Justice” to get an idea of how South Korea is grappling with the appropriate way to mete out punishment for underage perpetrators of crimes.

Anyone who is a victim of sextortion is encouraged to contact the FBI by calling 1-800-CALL-FBI. Tips can also be submitted online at tips.fbi.gov. Other resources are available at wannatalkaboutit.com.

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

-He visto que en las embajadas de corea del sur hay muchas mujeres protestando.

- Los medios coreanos estan más al pendiente de suga y army que del caso de nct, nth room, y otros casos que involucran a otros idol.

-Los medios están entretenidos viendo si ARMY esta dividido o no, cuando ya hay informacion de que las fans de nct quisieron encubrir el caso de su ex miembro, una campaña pagada por mucha gente.

-El acoso como el de Epik High ahora se lo quieren hacer a SUGA cuando hay cosas más importantes y peligrosas en Corea del Sur y es la seguridad de la mujer. No importa que digan que el presidente está tomando medidas cuando los medios desvian la atención.

-Perdón por meter otro tema, pero siento que está relacionado como cortina o distractor.

The level of punishment for sexual crimes in Korea is nothing compared to the US. ㅠㅠ