6 Must-see Korean Films + "Minari"

TRAIN TO BUSAN | PARASITE | THE WAY HOME | ONCE UPON A TIME IN HIGH SCHOOL | MY LOVE, DON'T CROSS THAT RIVER | MISS GRANNY | MINARI

This Sunday, “Past Lives” is up against films like “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” at the Academy Awards. While I don’t think Celine Song’s extraordinary movie will win for Best Picture, I do think she has a great shot at earning an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Of course, “Past Lives” is an American film set partially in South Korea and with half the dialogue in Korean.

But this got me thinking about some of my favorite Korean films that I wanted to share with you. (The anchor links will take you to each review if you don’t want to read them all. As always each film is rated on a scale of ☆ to ☆☆☆☆.)

🇰🇷 “Miss Granny” (수상한 그녀) ☆☆☆☆

🇰🇷 “My Love, Don’t Cross That River” (님아, 그 강을 건너지 마오) ☆☆☆

🇰🇷 “Once Upon a Time in High School” (말죽거리 잔혹사) ☆☆☆☆

🇰🇷 “Parasite” (기생충) ☆☆☆☆

🇰🇷 “Train to Busan” (부산행) ☆☆☆½

🇰🇷 “The Way Home” (집으로) ☆☆☆

🇺🇸 “Minari” ☆☆☆☆

“The Way Home”

☆☆☆☆

Grandmother (played by Kim Eul-Boon)

Sang-Woo (played by Yoo Seung-Ho)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

“The Way Home” is a bittersweet film about a young Seoul boy who is forced to spend the summer with his grandmother, who lives in the countryside. It’s not a quaint rural area that rich folks like to vacation in. Rather, it’s a small village where the bus comes on a irregular schedule and an angry cow chases little children. And even among the impoverished residents there, Grandmother is one of the poorest, with a small home that’s impossible to keep tidy (though she tries) and an outhouse that the child finds barbaric.

Sang-Woo’s mother drops the boy off and promises to return in a couple months when she has secured a new job. The grandmother’s hearing is intact, but she is unable to speak. She clearly understands that the child doesn’t want to be there. Sang-Woo cruelly and incessantly taunts her, referring to her as 병신/byeongshin — a derogatory word for stupid or retarded, which she is not. Bent over at a 90-degree angle from decades of hard labor and, most likely, lack of health care, she accepts what he says calmly. She has probably heard other children (and adults) say the same thing to her. But the hurt in her eyes is heartbreaking.

For much of the film, Sang-Woo is beyond bratty, dismissing his grandmother as 병신, partly because he is spoiled, but also because he is angry at having been left with someone he doesn’t know in an area where he doesn’t want to be.

His grandmother does everything she can to provide the luxuries that he wants. When he demands Kentucky Fried Chicken — which she has never heard of — she mistakenly thinks he is merely asking for chicken. She spends all day selling her vegetables to afford the live chicken that she brings home, butchers and makes into a delicious 삼계탕/samgyetang (ginger chicken soup). Out of spite, Sang-Woo refuses to eat it. But after she falls asleep, he gives in and hungrily tucks into the savory dish.

As the weeks progress, his heart opens up to her a little at a time. He begins to process the sacrifices she makes for things he previously took for granted. After selling squash from her garden, she buys him a new pair of shoes, while she wears her old ones that she stitches together to hold them in place. She treats him to lunch at a restaurant. While he is eating, he notices that his grandmother is only drinking water. When she pays, she is left only with a few coins for their bus fare.

The one element I wished had been altered was the daughter-mother relationship. A 76-year-old woman playing the mother of a woman in her mid-20s isn’t believable. Director/writer Lee Jeong-Hyang could’ve rectified this age discrepancy by making her Sang-Woo’s great grandmother instead. Kim Eul-Boon, who had never acted before, is a natural on screen with an expressive face and movements that convey her complicated emotions.

The acting at both ends of the age spectrum is simply beautiful. Kim and Yoo are convincing and viewers will be drawn into their relationship.

Film release: The 87-minute film released theatrically in South Korea on April 5, 2002.

Trivia: Kim Eul-boon had never acted before (or since), when she accepted this role at the age of 76. (At the age of 95, she died of natural causes on April 17, 2021.) Yoo Seung-Ho was just nine years old when he made his film debut in “The Way Home.” He would grow up to be a prolific actor, with roles in the K-dramas “Warrior Baek Dong-Soo,” “I’m Not a Robot,” “Memorist” and “Moonshine.”

Spoiler alert: As promised, his mom sends word that she’ll be taking him back to Seoul soon. Worrying about his grandmother, Sang-Woo threads a bunch of needles, knowing that her eyes are too weak to do so herself. He also teaches her how to read and write a few simple phrases: “I miss you.” “I’m sick.” Right before he leaves, he gives her cards where he has already pre-written messages along with handdrawn pictures illustrating what the words mean. If she is sick or misses him, mail the cards, he tells her, and he will come back to take care of her. Of course, he is 7 and is reliant on his mother to take him to his grandmother. And while his mom promises her mother that she will visit more often, the viewer is left wondering whether she will follow through, especially since it seems that she hadn’t visited her mother much prior to this. For whatever reason, she left her disabled mother alone to fend for herself.

“Minari”

☆☆☆☆

Jacob Yi (played by Steven Yeun)

Monica Yi (played by Han Ye-ri)

David Yi (played by Alan Kim)

Anne Yi (played by Noel Kate Cho)

Soon-ja (played by Youn Yuh-jung)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

(My “Minari” review originally ran in Teen Vogue. Like “Past Lives,” this is a U.S. film centering on ethnically Korean characters.)

For many children of immigrants, it can be humbling and almost unbearable to think about how much of our happiness is derived from our parents’ suffering. Koreans might categorize this uneasy feeling as han — a word that encapsulates the feeling of sorrow, resentment, and hope that has built up over generations.

Lee Isaac Chung’s beautifully-nuanced and semi-autobiographical film Minari offers a subtle release from that guilt. While it’s a specific story about one Korean American family, it also is a universal tale about everyone who has dreamed for a better future.

Jacob Yi (Steven Yeun) is positive that 50 acres of Arkansas farmland is the key to his family’s success. He will grow Korean vegetables on his farm, and he and his wife, Monica (Han Ye-ri), will continue to work as chicken sexers at the local factory. In a few years, after his farm turns a profit, they’ll quit their jobs and work full-time as farmers.

The problem is, he never told Monica this when they moved from their home in California. As she silently looks around their new home – a squalid trailer whose previous owner died by suicide – her face reveals her worries. The roof leaks. There is no Korean community nearby. And, most importantly, they are far removed from the nearest hospital, which is a necessity for their youngest child, David – a precocious seven-year-old moppet with wise eyes and a faltering heart.

David (Alan S. Kim) is Chung’s fictionalized alter ego. The only member of the Yi family who was born in the United States, he is an adaptable child who is befriended immediately at church by a boy who wants to know why David’s face is so flat. Likewise, his older sister, Anne (Noel Kate Cho), draws the attention of a girl whose ching chong introduction is less of an intentional racist barb than an ignorant microaggression.

At home, the siblings have become accustomed to hearing their parents argue loudly over money. David gets it into his head that his maternal grandmother — who he has never met — is somehow to blame. When he learns that she will be moving from Korea to take care of him while his parents work, he is filled with dread. Not only is he wary of having a stranger move into his life, but he also doesn’t want to share his room with her.

When Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung) arrives from Korea bearing gifts like gochugaru (spicy red pepper powder) and myeolchi (salted and dried anchovies), David is as disappointed as Monica is elated. Soon-ja is not like any of the grandmas from the 1980s television shows that had indoctrinated his young life. Where are the home-baked cookies? More importantly, he complains that she smells like Korea — a scent he can’t possibly know.

Soon-ja could’ve taken offense at his insults, but she laughs them off. She is amused by his antics and gives him leeway to become accustomed to her. Even after an incident when David intentionally serves her a disgusting drink to retaliate against the pungent medicine she brews for him daily, she can’t bear to see him punished. “Who cares if I drank it?” she tells Jacob, who is preparing to discipline the child. “It was fun!”

David is too young to understand that Soon-ja survived by herself in Korea. Widowed at an early age and with no son to take care of her, she provided for herself. And yet when she arrived in the U.S., she gave all her savings to Monica, who is embarrassed that she hasn’t been able to help her mother financially.

This has been a long-brewing source of contention for the Yis. They worked long hours in factories, but have no savings to show for it — not because they didn’t have money to put aside, but because Jacob sent it all to his parents. None of it was sent to Monica’s mother or put aside for their children.

“I’m the oldest son!” he tells her. “I have no choice.”

Monica’s frustration and anger is visible. But there’s not much she can say, because Korean women of her era knew going into marriage that it’s an eldest son’s duty to provide for his aging parents, even at his own nuclear family’s expense. I saw this occur in my own family. But where my mother differed from Monica is that she took charge of our finances, fulfilling my father’s duties as the eldest son while ensuring that there would be money saved for our college education.

As with many dreams before they are fulfilled, the Yi family live through nightmares that at times seem insurmountable. In an attempt to save money, Jacob dug his own well for his farm. When it dried up, he connected the crop irrigation to his home, which left the family with no water. Even when it’s obvious what has happened, he doesn’t confide in his wife.

Having survived much worse conditions during the Korean War, Soon-ja views this as a minor inconvenience. She takes David to the riverbank where they had planted minari – a Korean vegetable that flourishes with little fuss – and brings home buckets of water for the family to boil and use.

Earlier, she had told David and Anne not to scare away snakes at the riverbank, because they can be more dangerous to humans when they’re hidden from view. This is a recurring theme in Minari, with Jacob and Monica hiding their fears from one another, thinking it’s for the best to pretend they are unaware of what’s going on.

Chung is an astute filmmaker, who pays close attention to the smallest details. He has created a universally relatable film, while inserting elements that are specifically Korean. For instance, we never hear the parents use their Korean names. They introduce themselves as Jacob and Monica to the white congregation at church. But at home, they refer to each other as their children’s mother or father, as is customary for Koreans. Occasionally, they use yeobo — a Korean word that has morphed into a term of endearment between couples, but is an abbreviation for look here — which implies they are talking to a person who they take for granted will always be there for them.

Like most children, David and Anne are like the minari Soon-ja planted. They adapt well to their new surroundings without overthinking it. They’re friendly with the town’s religious outcast, because he works for their dad. They acclimate to Soon-ja, because they have to. They live where they live, because it’s where their parents chose.

Soon-ja also is resilient and never complains about their living conditions. She amuses herself by watching pro wrestling on TV. And when she hears her grandson complain that she’s not like other grandmas, she chooses to put a positive spin on it: You like grandma? Thank you! Yes, she could’ve misunderstood his words, but she understood the intended tone, just fine.

After the Korean War ended, but before South Korea built itself into an economic powerhouse known for its technology, BBQ and K-pop, my parents dreamed about immigrating to the United States, too. Migook, as the U.S. is known in Korea, literally translates into beautiful country. It is a nation full of wealthy and fair-minded Americans, they promised us. It had paved roads and was so clean that no one would dare spit on the streets like they did in Korea. America would give us opportunities we wouldn’t have back home.

Of course, this idealized version of America didn’t exist for us, just as it didn’t for the Yis. But what did exist was enough for us to grab onto and flourish.

“Train to Busan”

☆☆☆½ (out of ☆☆☆☆ stars)

Seok-Woo (played by Gong Yoo)

Sang-Hwa (played by Ma Dong-Seok)

Yong-Guk (played by Choi Woo-Shik)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

“Train to Busan” is a sociopolitical film disguised as a zombie horror thriller. Watching it in 2020 when much of the world was dealing with the coronavirus pandemic, the film had added meaning as to who and what were to blame for the unexplainable.

Seok-Woo is a successful funds trader who lives with his mother and young daughter, Soo-An (adroitly portrayed by Kim Su-An). Lonely at home and missing her mother, she tells her father she will travel to Busan by herself so she can spend her birthday with her mom. Busy with work and not wanting to take a day off, Seok-Woo begrudgingly agrees to accompany his child. They board the high-speed KTX train and … that’s where everything happens.

In this world of have and have nots — with the rich sitting in first class and the less rich sitting in the less-nice cars — two people board who don’t belong on the train. One is a frightened vagrant rambling bits and pieces about having seen everyone die. The other is a young woman with glassy white eyes who is convulsing. What the passengers don’t know is that like thousands of others, she was somehow contaminated by a leak from a bio-chemical factory. The result? Zombies, that can create more like themselves by biting into people’s flesh.

As some passengers rally to have the indigent man kicked off the train, others scramble to help the woman. After she attacks and bites a car attendant, all hell breaks loose. The passengers are now trapped on a train speeding along at about 200 miles per hour, with zombies begetting more zombies. And unlike the zombies of yore, these creatures are lightening fast.

Luckily, they’re not very bright. Though they will fight as hard as they can to attack humans, they don’t know how to unlock closed doors. They also don’t do well in the dark. If they can’t see their prey, they don’t attack.

There are some astounding moments juxtaposed together. As passengers watch in horror as zombies attack passersby outside, a politician appears on TV telling the public to stay calm … that everything is under control … and not to believe all the unsubstantiated rumors floating around. They’re being told not to believe what they’re witnessing with their own eyes.

While most passengers go into fright or flight mode, Seok-Woo’s priority is keeping his daughter alive. He teams up with muscular father-to-be Sang-Hwa and high school baseball player Yong-Guk to figure out how to escape the zombies. In true action-hero style, they each have a female to protect: Sang-Hwa’s pregnant wife, Seong-Kyeong (played by Jung Yu-Mi, the star of 2019’s “Kim Ji-Young, Born 1982”); Yong-Guk’s sweetheart, Jin-Hee (played by former Wonder Girls‘ Sohee); and little Su-An.

But though it seems the women are waiting for the men to rescue them (and they often are), there are small moments that give a glimmer of what the female characters could’ve done. Seong-Kyeong gets pro-active, sticking newspapers on the glass doors so the zombies can’t see them. Jin-Hee was familiar with the baseball world. I kept waiting for her to pick up a bat and take action. Sadly, that never happened.

The film did a great job of depicting how people deal with death during unthinkable times. When your loved one is infected and your only option is to perish (as a human being) with them or kill them so that you (and others) can survive, what would you do?

Meta moment: Gong Yoo fans should check out “Goblin,” when his character goes on a date to the movies. Their film of choice? “Train to Busan.” His titular character turns out to be a bit of a fraidy cat who screams throughout the movie.

Release date: After premiering at Cannes on May 13, 2016, the film opened in South Korea on July 20.

Running time: 118 minutes.

Spoiler Alert: Very rarely does the star of the film die. But the trio of men who lead the fight against the zombies don’t survive. The vagrant also sacrifices himself so that others may live.

Kim Eui-Sung, who was perfectly evil in “Mr. Sunshine,” plays a rich muckety muck, who believes he is better than others and that he deserves to survive more than anyone else. He bosses around the train staff into getting his way. And he incites his fellow passengers into a state of paranoia that has them turning on each other. He eventually succombs to zombiehood, but not before taking a bite out of Seok-Woo, who is aware of what will happen next. He says goodbye to his daughter, who begs him to stay with her. Watching her accept the blame for all this (for wanting to visit her mother in Busan) was heartbreaking. Chances are, she was safer on the train with her father than at home with her grandmother, who, incidentally, got bit. Seok-Woo hugs her and tells her to stay with Seong-Kyeong and then he throws himself from the train. The film ends after Seong-Kyeong and Su-An walk through a tunnel, where they are met by armed military.

One of the most memorable parts of the film came near the end, when two elderly sisters are separated. One makes it back on the train to safety. The other has become a zombie. As the human sister watches her fellow passengers turn on each other — banishing a small group out of fear that they may have been infected — she looks at the group of zombies that has infiltrated the train. She spots her sister and slowly opens the door. The scene seemed nonsensical at first. Why would she willingly become a zombie? To me, it was a sign that she saw no difference between the zombies and some of her fellow passengers, who were willing to let others die to ensure their own safety. Neither valued human life.

“My Love, Don’t Cross That River”

☆☆☆☆

Jo Byeong-Man

Kang Kye-Yeol

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

“My Love, Don’t Cross That River” is a love story that shows there is beauty to be found in everyday life, even with death looming.

A languid documentary about an elderly couple that has been married for more than 70 years, the 86-minute film — which is both tranquil and heartbreaking — is deftly directed by Jin Mo-Young.

Jo is 98 and Kang– who was his child bride — is 89.

They laugh, argue and flirt with each other; and when they fall asleep, they still hold each other’s hands.

Jin spent 15 months in 2012-2013 filming the pair as they went about their everyday lives.

But the film starts and ends with mourning. And because we see Kang softly sobbing, we know within the first minute of the film that her husband has died.

As I listened to her gut-wrenching cries, I had a morbid thought: Did Jin stay with them for so long because he was waiting for death to fall upon one of them? That’s not something I can answer.

This documentary moves at a measured pace, to parallel the couple’s movements. Some of the scenes are so lush and gorgeous they look like they could be clips from a Korea Tourism commercial. I agree with some critics that the colorful, matching hanboks that the couple wears look like they were chosen specifically because they appear so vibrant on camera. But, I didn’t care.

Viewers witness other aspects of life that are raw and familiar in their everyday intensity. At Kang’s birthday party, their six adult children (and their kids) gather together to celebrate. After a long day of cooking and cleaning up afterwards, one of the children says they should just go out to eat next time. This comment turns into a heated verbal fight, as two of the siblings bitterly argue about who has sacrificed more for their parents. Jo and Kang look on helplessly. I imagine they felt sadness and guilt that their survival meant that their children had to adjust their lives to help them.

It’s an untold truth that assisting elderly parents is difficult, no matter how much you love them. As independent as Jo and Kang are, there are some things they cannot manage alone — mundane things like hanging a heavy mirror on a wall; and important things, like getting to the hospital for emergencies.

Some of the most poignant moments are the quiet ones, as they talk about their history together. Kang was just 14 when Jo, who had been orphaned, came to work for her family. They married (her youthful age was not uncommon during that era), but he wouldn’t initiate intimacy with her, she said. He waited for her to literally grow up. After three or four years, it was she who let him know she was ready to live as husband and wife. She says she was always thankful to him for giving her the gift of time. She would give birth to 12 children, but six would die from diseases such as measles.

As she buys six children’s 내복 (pajamas), she tells the saleswoman to make sure they’re roomy. They are for her deceased children to wear. When she or her husband dies, these clothes will be burned (along with the deceased’s) and that soul will “take” the children’s clothing with them so the babies can stay warm. Her voice breaks when she says she wishes she could’ve given them these lovely clothes when they were still alive.

My heart broke then and there.

But the memory of that scene added some comfort when Jo died. In my head, I knew differently. But in my heart, I felt a sense of peace that Jo would be reunited with their babies. In death, the children would finally get to wear the cozy clothes their mother had always wanted them to have.

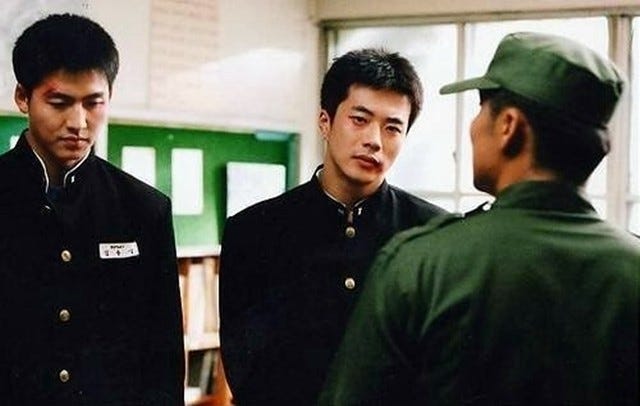

“Once Upon a Time in High School”

☆☆☆☆

Hyun-soo (played by Kwon Sang-woo)

Woo-shik (played Lee Jung-jin)

Eun-joo (played by Han Ga-in)

Jong-hoon (played by Lee Jong-hyuk)

Hamburger (played by Park Hyo-jun)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

In the U.S., “Once Upon a Time in High School” was released as “Spirit of Jeet Kune Do: Once Upon a Time in High School.” While it has its share of fight scenes that incorporate taekwondo, the South Korean film is really more about a boy’s survival through one of the roughest years of his life.

Hyun-soo’s father is abusive to him at home. His mother, who moved the family to Gangnam (anticipating that it would become a coveted neighborhood in Seoul), is never shown. We can assume that she is working long hours. And he has to transfer to Jungmoon — an all-boys high school — that has earned a brutal reputation that turns out to be well earned.

Released in 2004, the film is set in 1978. During this time-frame, South Korea was ruled under the brutal dictatorship of Park Chung-hee (the father of Korea’s only female president, Park Geun-hye). The movie depicts a bleak period where students had few rights and teachers could beat them at will.

There’s a trickle down factor to that kind of abuse. The boys settle their differences not with words, but with fists, chairs and bats.

At Jungmoon, soft-spoken Hyun-soo is shocked by the behavior of his classmates. Jong-hoon and his gang of bullies rule the school.

Thanks to his height, speed and ability to play basketball, he is befriended by his class’s leader, Woo-shik. The son of a TV star, Woo-sik is handsome, charismatic and confident. The two bond over their love of Bruce Lee films. Woo-sik is a good martial artist who never backs down from a rumble. While Hyun-soo was trained in taekwondo by his grandmaster father and had long emulated the moves he saw Lee execute on screen, he is meek and is reticent to fight back.

When Woo-sik starts dating Eun-joo, the girl Hyun-soo has been pining for, their friendship is fractured. Honestly, if Hyun-soo had told Woo-shik to back off, I believe he would’ve. He valued Hyun-soo’s friendship. Girls were just a game for him.

After watching Woo-shik get beaten up by Jong-hoon and seeing that the school did nothing about it, Hyun-soo can’t take it anymore. He contemplates suicide, but opts instead to train himself to hone his martial arts skills.

Armed with his nunchucks, Hyun-soo lives out his Bruce Lee fantasy, successfully taking on not only Jong-hoon, but also his cronies. While his father apologizes profusely in public for his son’s behavior, Hyun-soo says in the voiceover that his father never hit him again after that.

The takeaway from this movie isn’t that you must beat your opponents to earn their respect. Rather, it’s that when there’s no way to battle a corrupt system, you have to fight back to make your enemies fear you.

“Once Upon a Time in High School” isn’t a perfect film, but it’s a good one. Though the male leads all look too old to pass for high school juniors and seniors, they are convincing nonetheless.

The bromance between Hyun-soo and Woo-shik was much more interesting and layered than the love triangle. I would’ve liked to have seen how their friendship progressed through their collegiate years.

Release date: January 16, 2004.

Running time: 116 minutes.

“Parasite”

Kim Ki-taek (played by Song Kang-ho)

Kim Ki-woo (played by Choi Woo-shik)

Kim Ki-jeong (played by Park So-dam)

Gook Moon-gwang (played by Lee Jung-eun)

↑Note: Korean names denote the surname followed by the given name.

“Parasite” made film history as the first South Korean movie to win Oscars for Best Director for Bong Joon-Ho and Best Picture. Everyone already knows the plot of the film, but what I wanted to delve into were some of the key moments from the film that still stand out in my mind.

FYI, the following is full of spoilers. So do not read any further if you don’t want to know some of the storyline:

♦ Early on in the film, we see the Kim family sitting in their squalid basement apartment, folding pizza boxes to earn money. What’s never discussed is how the patriarch supported the family in earlier years. The days of salary men working for the same company until they retired are long gone. Men and women in their 50s often lose their jobs, because they’re too expensive for employers to keep around. They’re replaced by younger, less experienced employees who can be paid less. When I was in Korea during one trip, I hired a driver, whose previous position had been in managerial for a well-known airline. Because he had children to put through college still, he had to reinvent himself with a new career. Because he spoke several languages, he was in demand to drive around tourists. But he said many people he knew opened small restaurants or shops to earn money for their family after their forced retirement.

♦ The friendship between Ki-woo and his friend, Min-hyuk (played by Park Seo-Joon), appears to be genuine on the surface. But when you look at the dynamics, they’re using each other under the pretense of being helpful. Min-hyuk is going overseas to study and tells Ki-woo that he wants to start dating the rich girl he tutors once she enters college. (She’s currently a high school sophomore.) He says he recommended Ki-woo as his replacement, not only because he’s smart, but because he’s trustworthy. In other words, Min-hyuk doesn’t trust his rich, horndog friends not to make a move on the girl. But he trusts his friend, because what could Ki-woo possibly offer a rich, beautiful girl? Min-hyuk doesn’t view Ki-woo as competition, because of the latter’s lowly station in life.

During a pivotal scene where everything is going wrong for the Kims, Ki-woo asks his sister what Min-hyuk would do in their situation. She says Min-hyuk would never be in their position. That statement spoke volumes about their class difference and lack of privilege.

♦ After ingratiating himself to the wealthy Mrs. Park, the first thing Ki-woo does is charm her daughter. The two are making out in no time. She would’ve been about 15 or 16. He had already served mandatory military duty and failed his college entrance exam several times. So he was probably in his early to mid 20s. The class difference between the two was noted, but no one made a big deal about a man macking with a teenage child. Ew. For Ki-woo, the girl is less of a romantic interest than a means to raise his social position in life. He even tells his family the same thing Min-hyuk told him: once the girl enters college, he will officially date her. (Remember…when Min-hyuk had spoken of his interest in the girl, Ki-woo didn’t think it was odd that his adult friend wanted to date a child.)

♦ Once he has embedded himself into the Park household, Ki-woo brings in his sister, Ki-jeong (aka Jessica) as an art instructor for the Park’s younger child. She impresses Mrs. Park with her fake diploma from Illinois State. This is where I literally laughed out loud in the movie theater. There is no upper echelon Korean family that is going to be impressed by Illinois State. This has nothing to do with the quality of the school, but speaks more to the snobbery of a certain subsector of Koreans who look for brand names like Harvard, M.I.T. and Stanford when it comes to their children. (One of my younger relatives was a coveted tutor, because she was a student at Korea’s top school: Seoul National University.) This seemed to be Bong’s way of letting his Korean viewers know exactly how gullible and clueless the Park family was.

A few years ago, Korean American singer and former “American Idol” contestant John Park was a guest on “Running Man” — the same episode that BTS‘ RM appeared on. It was a segment about the smartest K-pop idols. Everyone acknowledged that RM, with his 148 IQ, was a genius. But the regular cast members gave Park a hard time, joking about his education. Kim Jong-Kook even insinuated that Park wasn’t that bright and that American schools weren’t difficult to get into. For a frame of reference, Park attended Northwestern University, which is ranked No. 9 (in the United States), according to U.S. News & World Report’s annual college ranking. Kim graduated from Dankook University, which isn’t one of South Korea’s prestigious SKY schools. Dankook is ranked No. 35 in South Korea. But Kim had never heard of Northwestern and he was comfortable enough about what he perceived the school to be to tease Park about it.

I can’t even imagine what Kim Jong-Kook would’ve said about Illinois State.

Release Date: “Parasite” premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 21, 2019. It opened in South Korea on May 30, 2019.

© 2024 JAE-HA KIM | All Rights Reserved

Good list, but I loved My Sassy Girl.

What a fantastic list!! Parasite is such a magnificent film, so expertly made. I remember being floored that a Korean movie won best picture. I never thought I'd ever see that in my lifetime.

If I may recommend a Korean film that is dear to my heart, it's "Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring." Such an evocative, strange movie. It's been decades since I saw it, yet I remember so many scenes so vividly.

Happy Oscars! Fingers crossed for Celine Song, who absolutely has a chance here.